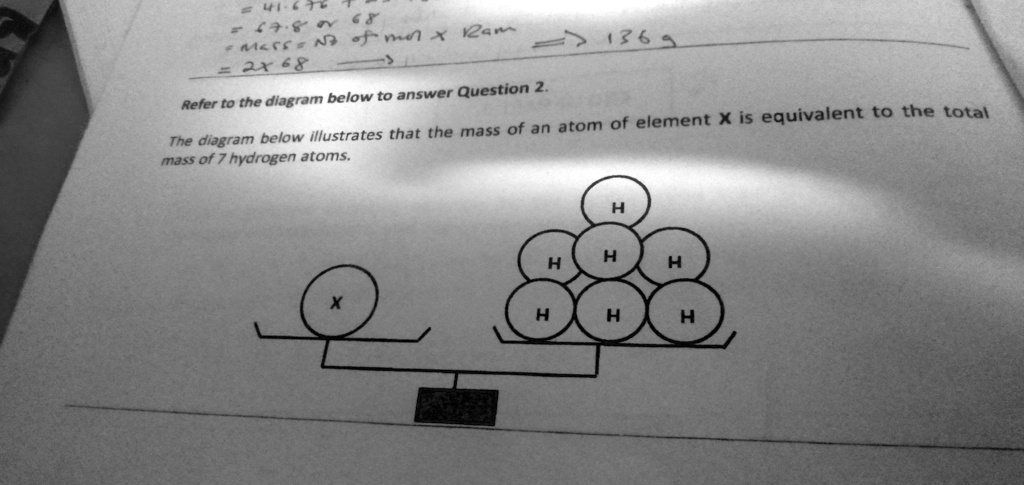

= 41.676 = 67.8 or 68 mass = No of mol x Ram = 2x68 Refer to the diagram below to answer Question 2. The diagram below illustrates that the mass of an atom of element X is equivalent to the total mass of 7 hydrogen atoms. H H H H X H H H

The Correct Answer and Explanation is:

Answer:

The relative atomic mass of element X is 7 atomic mass units (u). On today’s carbon-12 scale that corresponds to the element lithium (Li), Aᵣ ≈ 6.94, the only naturally occurring element whose average atomic mass rounds to 7.

Explanation

A balance simply compares masses. In the diagram one pan holds a single atom of unknown element X, while the opposite pan holds seven separate hydrogen (H) atoms. Because the beam is shown perfectly level, the two pans exert equal gravitational forces; in other words, their masses are identical.

Chemistry expresses individual-atom masses on the relative atomic-mass scale. On the historical hydrogen scale the mass of one H atom is assigned a value of 1. (In modern practice we use one-twelfth of a ¹²C atom as 1 u; because a hydrogen atom is 1.008 u on that scale, the two systems differ only very slightly for lightweight atoms.) When a single X atom balances seven hydrogen atoms, its mass must be seven times larger than that of a single H atom: m(X)=7×m(H) ⟹ Ar(X)=7m(\text{X}) = 7 \times m(\text{H}) \;\Longrightarrow\; A_{r}(\text{X}) = 7

Relative atomic mass is a dimensionless ratio, so no units need be attached beyond the conventional “u”. Converting to the carbon-12 scale: Ar(X)≈7×1.008 u=7.06 uA_{r}(\text{X}) \approx 7 \times 1.008 \,\text{u} = 7.06 \,\text{u}

Consulting a periodic table, the lone element whose naturally weighted atomic mass is essentially 7 u is lithium. (Lithium’s average of 6.94 u reflects its two stable isotopes, ⁶Li and ⁷Li, in a 7.6 : 92.4 mixture.) Therefore element X must be lithium.

This simple comparison illustrates a key idea in atomic theory: although atoms are unimaginably small, their masses keep fixed ratios — a fact that underpins the law of definite proportions and stoichiometric calculations. Early chemists such as Dalton and Cannizzaro deduced entire atomic-weight tables by measuring how much of one substance balanced another, exactly like the schematic scale you see here. Even today, high-precision mass spectrometers perform a conceptually identical task, but with far greater sensitivity, establishing the relative masses of isotopes that define the modern periodic table.