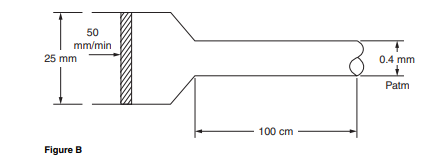

A saline solution (density 1050 kg/m3) is ejected from a large syringe, through a small needle, at a steady velocity of 0.5 m/s. Estimate the pressure developed in the syringe. Neglect viscous effects. Assume that the velocity of the fluid in the large syringe is approximately zero, when compared with the velocity in the needle.

The Correct Answer and Explanation is:1

To estimate the pressure developed in the syringe, we apply Bernoulli’s equation between two points:

- Point 1: Inside the large syringe (where velocity is approximately zero)

- Point 2: At the needle exit (where velocity is 0.5 m/s and pressure is atmospheric, PatmP_{\text{atm}})

Bernoulli’s Equation:

P1+12ρv12+ρgz1=P2+12ρv22+ρgz2P_1 + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_1^2 + \rho g z_1 = P_2 + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2 + \rho g z_2

Assumptions:

- Neglect elevation change: z1=z2z_1 = z_2

- Neglect viscous losses

- v1≈0v_1 \approx 0 (velocity in the syringe)

- P2=PatmP_2 = P_{\text{atm}}

- v2=0.5 m/sv_2 = 0.5 \, \text{m/s}

- ρ=1050 kg/m3\rho = 1050 \, \text{kg/m}^3

Simplified Bernoulli: P1=Patm+12ρv22P_1 = P_{\text{atm}} + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2 P1−Patm=12⋅1050⋅(0.5)2P_1 – P_{\text{atm}} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 1050 \cdot (0.5)^2 P1−Patm=12⋅1050⋅0.25=131.25 PaP_1 – P_{\text{atm}} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 1050 \cdot 0.25 = 131.25 \, \text{Pa}

Final Answer:

P1=Patm+131.25 Pa\boxed{P_1 = P_{\text{atm}} + 131.25 \, \text{Pa}}

Explanation

The pressure developed in a syringe during fluid ejection through a narrow needle can be estimated using Bernoulli’s principle, which relates pressure and velocity in fluid flow. In this case, a saline solution with density 1050 kg/m31050 \, \text{kg/m}^3 is pushed through a syringe and needle system. The fluid in the large syringe moves very slowly compared to its velocity at the needle exit (0.5 m/s), allowing us to simplify the analysis.

Bernoulli’s equation assumes conservation of mechanical energy for an incompressible, non-viscous fluid along a streamline. Since we’re told to neglect viscous effects and elevation change, the pressure in the syringe must account for the kinetic energy the fluid gains as it accelerates through the narrow needle.

At the needle exit, the pressure is atmospheric. Inside the syringe, the fluid is almost stationary, so all the energy that appears as kinetic energy at the exit must have come from the pressure in the syringe. Mathematically, this means the syringe pressure must be higher than atmospheric pressure by an amount equal to the kinetic energy per unit volume of the fluid, which is 12ρv2\frac{1}{2} \rho v^2.

Substituting the given values into this expression yields a pressure difference of 131.25 Pascals above atmospheric pressure. This extra pressure is what pushes the fluid through the narrow opening at the specified velocity. Despite the simplicity of the result, it highlights how modest pressure differences can produce noticeable flow speeds, especially in low-viscosity fluids and narrow tubes.